AN INTERVIEW WITH JÓNSI OF SIGUR RÓS ON HIS EXHIBITION AT TANYA BONAKDAR GALLERY IN LOS ANGELES

Jónsi. Photo by Paul Salveson. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

In a compelling conversation with Jónsi, artist and musician renowned for his contributions to Sigur Rós, we delve into the immersive world of his latest exhibition, "Vox," showcased at the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles. This unique exhibition merges the metaphysical with the material, offering visitors a holistic sensory journey. Through a combination of sculpture, sound and light installations, and evocative scents that mimic the Nordic climate of his native Iceland, Jónsi invites audiences into a space where art transcends visual boundaries, engaging multiple senses to create a profound connection with the ethereal landscapes that have deeply influenced his artistic and musical endeavors.

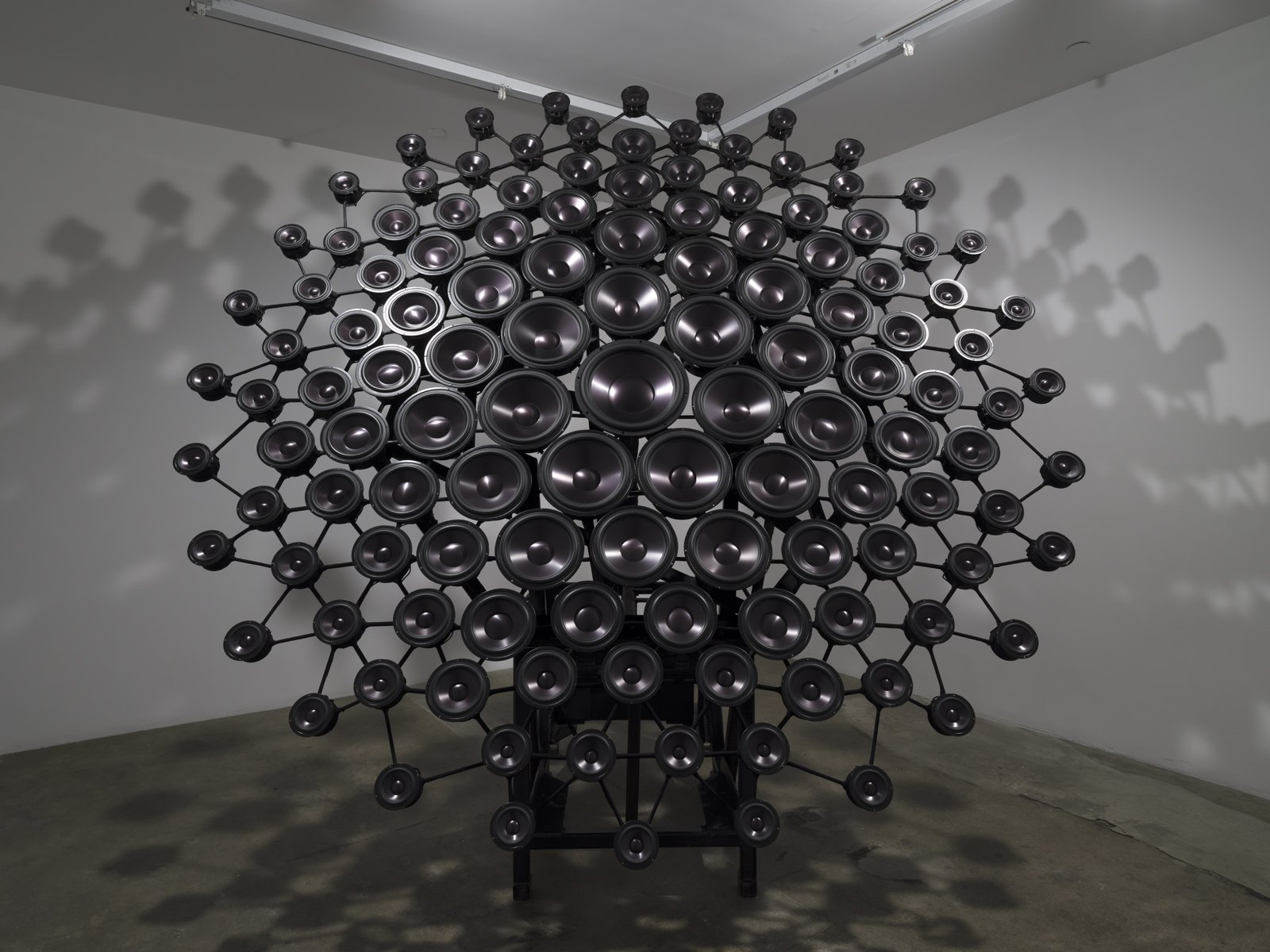

Jónsi, Silent sigh (dark),2023. Speakers, metal, electronics. 117 x 114 x 69 inches; 297.2 x 289.5 x 175.2 cm. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

From an art historical perspective, Jónsi's oeuvre manifests a dialogical relationship with seminal works that have traversed the boundaries of performance art, technological innovation, and the whimsical tableau of contemporary installations. His interactive installations reverberate with the performative élan characteristic of artists like Doug Aitken and Nikita Gale's dynamic interventions, where spectatorship is subverted into active participation. This echoes the Fluxus movement's dismantling of the traditional art audience dichotomy.

Jónsi.Vox, 2023. 8 -channel sound installation, speakers, LED screens, fog, scent (Vetiver root, galbanum, angelica root, iris root/ orris, cis-3-hexenol). Dimensions variable. Duration: 25 minutes. Edition of 3, 1 AP. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

Moreover, Jónsi's adept employment of avant-garde technology as a medium recalls the pioneering ethos of artist Nam June Paik, often celebrated as a progenitor of video art. Paik's radical experiments with electronic media and sculpture may serve as a precursor to Jónsi's endeavors to transcend the conventional sensory lexicon of art, promoting a synesthetic fusion of sight, sound, and scent that challenges and expands the spectator's perceptual parameters. Jónsi’s productions, often site-specific and ephemeral, invoke the legacy of Situationist détournement, inviting the audience to encounter the sublime and the unexpected within the quotidian.

Jónsi. Var (safespace), 2023. 8 -channel sound installation, speakers, electronics, scent (cis-3-hexenol). Installed dimensions: 98 x 68 x 24 inches; 249 x 172.7 x 61 cm. Duration: 6 minutes. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

INTERVIEW

AMADOUR: How's your day so far?

JÓNSI: It's good. It's intense and stressful, but good. I had a meeting with my Iceland gallery at nine in the morning for an exhibition there in June. I'm still on Iceland time and am now driving to my studio space in Downtown LA. Today's supposed to be super rainy out there on the highways.

AMADOUR: Thank you for speaking with me today and agreeing to an interview.

JÓNSI: Are you starting a magazine or something?

AMADOUR: I am. It's called WHO IS SEEN Magazine, and you are among the first interviews. It's about uncovering different dynamics in each interviewee that may be overlooked or not seen, focusing on art, music, fashion, beauty, etc.

JÓNSI: Amazing.

AMADOUR: I loved your show at Tanya Bonakdar in LA and also your show “Obsidian” at the gallery in New York City a few years ago. You are like a magician, and your show is a riveting experience. You did such an incredible job!

Jónsi, Sólgos (Solar flare), 2021. Chrome discs, LED lighting, aluminum, directional speakers, subwoofer, geosmin scent. 84 x 84 x 29 inches; 213.4 x 213.4 x 73.7 cm (sculpture)Dimensions variable (installation)Duration: 10 minutes, 4 seconds. Edition of 1; 1 AP. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

JÓNSI: Thank you for coming; walking you through the space was great.

AMADOUR: I know you come from a music background with your band Sigur Rós. When did you begin to feel that you could experiment with different media, and where did you find the liberty to delve more deeply into the visual experience?

JÓNSI: When you grow up in Iceland, it's a pretty small community. Like in Reykjavik, there are a lot of people like artists and musicians, and usually, people are doing something creative. All of my sisters are artists, like graphic designers, photographers, and stuff like that. So yeah, you're constantly surrounded by artists, and before I started being serious about music, my main thing was painting in school. I used to love painting and drawing, but then slowly, music takes over, and you, like, you know, start the band, and that becomes the main focus of your life. And it wasn't until I moved to LA, where I had more time for myself, far away from my friends and family, and jumped into more arts-related projects.

AMADOUR: What I relish about your exhibition are the numerous scents that morph as you walk around the various pieces. Can you tell me more about their origins, how these olfactory compositions impacted your life, and your journey into perfumery?

JÓNSI: I've been obsessed with scent and smell all my life. And I've been doing maybe serious perfumery for about 15 years now.

AMADOUR: Oh wow. That's a long time! <laugh>

JÓNSI: I wouldn't say I like perfumes per se. I think they're all too this or that, I don't know, too flowery, too grandma. I started making scents because I wanted something to wear that I liked. And then I realized it's complicated and not easy at all. So, I began collecting essential oils, forming my blends, and trying different trials and errors. Then I realized there's another world called aroma molecules where you can focus on your scent and design it from bottom to mid-top notes. So it's an endless school. I'm still interested in this and like learning, but it's not for everybody because it is like a slow movie and honestly one of the most challenging things I've done in my whole life.

AMADOUR: Do you make them in your studio?

JÓNSI: Yeah, I have a perfumer's lab in my basement. There are hundreds of aroma molecules, sensual oils, and scents. I included them in the exhibition to bring together all the senses, including working with music and sculpture. I want to trigger all the senses when the viewer enters the gallery. It adds so much flavor to the experience combined into one moment, translated through music and light.

AMADOUR: I want to speak about Vox (2023). Where did the inspiration come, are you considering other artists who work with light and sound?

JÓNSI: I don't know anything about art or art history, and it's like a blessing and a curse. I know more about music now because I've been in it for so long. I've been in it for my whole life. We have been a band for 30 years. But in art I am inspired by Icelandic artists like Olafur Elliason, who I would say is a light artist. He does a lot of video installations, which is impressive too. Maybe you can tell me what you think?

AMADOUR: I immediately think of the etherealness of James Turrell's Twilight Epiphany (2012), Skyspace. Also, Anthony McCall and Doug Wheeler come to mind, with their works shifting with the tonalities of light from various angles. While immersed in the lights of your work, Vox, I wondered why you chose to build a seat in the center of the room.

JÓNSI: I mean, good question. I was thinking of either putting the seat in there or just having nothing in there so you could walk around, and maybe that would have been better. I like having a seat in the middle because it's a neutral ground where you can view all the screens. Maybe I should have put it on the sides or something. I don't know. <laugh>. Interesting point.

AMADOUR: As our exhibition walkthrough coincided with a group tour from the Tom of Finland Foundation, I didn't initially sit down and instead wandered around, getting lost in the immersive experience of the lights and sounds emanating from the walls. One of the guys on the tour scolded me for not sitting down. <laugh> He said, “The artist put a seat in here for a reason. Do you realize it's intended for you to sit down?” And I was like, “Oh my god,” so I sat down, and it was a wonderful experience. I also went back to see your show with my dear friend, Yuko Hasegawa, Director of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan. Have you been there?

JÓNSI: No, I haven't yet.

AMADOUR: The museum is one of the most extraordinary spaces ever. It was designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architects Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, who also designed the New Museum in New York City. But I brought her to look at your space because I was so excited about the show. We went together, and she was so curious about the piece Silent Sigh (dark) (2023). She was saying to me that it feels like a living sculpture. And so, how do you articulate movement in your sculptures, and where did you come up with the idea to use the speaker as a visually anatomical attribute?

Jónsi, Hrafntinna (Obsidian), 2021. Fifteen-channel sound installation, chandelier, speakers, subwoofers, carpet, fossilized amber scent. Dimensions variable. Duration: 25 minutes, 33 seconds. Edition of 1; 1 AP. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

JÓNSI: This stems from experimentation and just trying things out and seeing what works and doesn't. Much time goes into it more than I would've thought, like researching material, how things work, why they work, and maybe why they don't. Through much trial and error, I just went for it, knowing I wanted to use speakers in my sculptures. Initially, I wasn't thinking about it moving but more about sound. When the larger speakers began to move, I hoped they wouldn't make any sound. However, when you have a direct current playing through them, they make this electric sound. That's the sound you heard. When you play a super low frequency, you see the movement but can't listen. They don't play anything.

AMADOUR: Considering how you use your voice to make the sounds in Vox, what was the recording process like? I remember you telling me that you use AI voices and your own. As a musician, I'm curious about what you did.

JÓNSI: Vox translates to voice, and I think this work is about the voice. The first thing I did was multiply myself like a choir of voices to stack up the vocals.

AMADOUR: What mic did you use? Did you use a nice mic, or did you use whatever?

JÓNSI: Both. I have a Shure SM7B, a basic mic, and also a fancy one, a Neumann U 47, a tube microphone, an exquisite microphone, but you know, an expensive one. Anything works, really, and you can do anything you want.

AMADOUR: How many layers did you add to each vocal stack?

JÓNSI: It's a shit ton of voices. When I do choir stuff, one of the main things I do is layer four voices, like on one line, sing that four times, then do a harmony with that four other times, and then another harmony four times. So you have sixteen voices in the end, which are tons of voices. Then you do another sixteen voices, which stacks up pretty quickly. But it's fun because when you have 52 speakers and lots of different outputs, you can kind of play with that.

AMADOUR: Did you edit the voices with any plugins? Or was it just an unfiltered vocal take?

JÓNSI: I always like a pure, organic, unaffected voice. In this, there are many spectral sounds; I used Antares Harmony Engine and a lot of the pop stuff people play around with. I dropped my voice into AI tools, and it would spit out many different versions of my voice and the phrase.

AMADOUR: That's so cool. I know Grimes made her program, GrimesAI-1 Voiceprint, where creators can upload their voices and transform them into hers. What AI tools do you use?

JÓNSI: It's called Synplant. I drop in samples, and it spits out different versions of that sound and tries to recreate my voice in a synthesized version. You get wacky results.

AMADOUR: Did you mix the sounds yourself?

JÓNSI: I'm alone ninety percent of the time and pre-mix everything well. I've been doing it for so long, but I have my friend Paul Corley, who lives in LA, and he helps me fine-tune it because when you come into the gallery space, it's a very different experience from the recording studio where there are a lot of concrete walls and echoes. I remember my exhibition at Tanya's "White Out" a few years ago. I had no carpet on the floor, and there was this crazy echo.

AMADOUR: Which comes first for you, the audio or visual component?

JÓNSI: I start with music. Then I see everything else in my mind, like how the screens will look, their size, and everything. We have a guy working with me, Damon Dorsey, who is helping me in my space downtown. Before we made anything, he drew everything up on SketchUp to know the dimensions and how it would look. It's essential to see the scale, how it's going to work, if it's going to work, and stuff like that. Then, I work to translate sound to a visual frequency.

AMADOUR: Regarding your multi-speaker work Var (safespace) (2023), the title alludes to assembling a safe space.What does this term mean to you?

JÓNSI: The first idea was to create a blanket you can crawl under like a kid. It's about hanging a blanket over a piece of string, where you're in your own space, your “safe space”, inside your little fort. So that's where the warm, crackly kind of ASMR-like rain on the roof and fire-crackling wounds come from; there are also bird sounds. It's basically like a kind of processed field recording. I was looking into a safe space connected to and originating from LGBTQ+ culture; the term "safe space" refers to places intended to be free of bias, conflict, criticism, or potentially threatening actions, ideas, or conversations, including any marginalized minority, gender, ethnicity, or religion, where people can come together to communicate regarding their shared experience. It was stunning, and that expanded my idea of it.

AMADOUR: You're creating a safe space for people to be themselves. They can go into the darkness to gather their thoughts or be submerged in the light. What do you feel you learned the most from doing this show?

JÓNSI: The most significant question after all this is whether I should keep doing it. It was so stressful. <laugh> It's stressful to be an artist. I've been doing music my whole life. When you have big ideas, it's hard to make them happen, especially when you don't have the means and the money to put the show up before the installation in the gallery. So, basically, we are just plugging everything in at the last minute; I didn't know if it would actually work together or if all the screens would work. There were just a lot of unknown questions and stressful situations. There's a lot of extremely intense stuff behind the scenes. But you know, it's also rewarding at the end.

AMADOUR: I appreciate your honesty and humility. People sometimes try to make it seem like it’s all super easy in art. Any version of creation comes from exploring, seeing if things will work, how things will turn out, and being okay with the unknown. That's what makes your work so memorable and connected to the audience. Everyone I've spoken to who experienced your show agreed its unforgettable and meaningful, so I want to thank you.

JÓNSI: I guess it's the biggest reason you do it. When I was a kid, I went to a show and saw something inspiring, the most essential part.

AMADOUR: What was your first art show that you remember going to? Was it at the museum there in Reykjavík?

JÓNSI: I never really went to see art as a kid. My family was not into art, theater, or ballet; I didn't see anything when I was a kid, so I didn't go to many art shows. It's mainly just in the last few years that I've been going to galleries.

AMADOUR: I relate to you, even though I might seem like an art person. I only went to my first museum when I was thirteen or fourteen.

JÓNSI: Well, that's early.

AMADOUR: It is, but some people grow up with it.

JÓNSI: True. I know. I was not one of them. But maybe that's good.